|

|

|

|

| May 18, 2024 |

|

Japanís quake still poses puzzles

One year ago, the earthquake that struck Japan literally changed the spin of our planet and the length of our day ó but today, the biggest mystery surrounding the event is what didn't happen: Why wasn't the Tohoku earthquake even bigger?

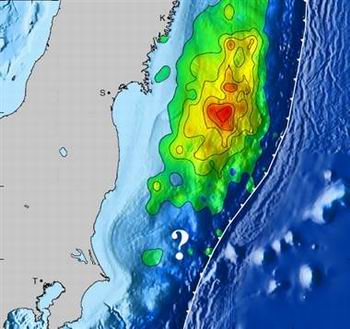

"We really don't know what's going to happen in the future," said Thomas Heaton, director of Caltech's Earthquake Engineering Research Laboratory. "And by the way, one of the big questions nobody seems to be talking about is ... why was Tohoku so small? Where's the rest of it? Was this a foreshock? We don't know that. Honestly, it was mostly in the northern part of the [Japan] trench. The southern part of the trench doesn't seem to have gone." It may sound strange to talk about a magnitude-9.0 quake and tsunami as something that's mystifyingly small. But the way Heaton sees it, the unusual scenario that played out on March 11, 2011, shows how much we still have to learn about how earthquakes work. Moreover, it shows that scientists may not fully understand the mechanism of seismic shocks for the foreseeable future. "The most obvious lesson learned is to plan for the unexpected," Heaton said. SURPRISES FROM THE JAPAN TRENCH Scientists have long known that the Japan Trench, where the oceanic Pacific Plate dives beneath the continental Okhotsk Plate, was seismically active. It's part of the "Pacific Ring of Fire" that runs like a horseshoe around the ocean's edge. But scientists and engineers thought the trench wasn't capable of generating earthquakes that big ó and so they designed structures such as seawalls and nuclear power plants to fit what they saw as prudent probabilities. "The real problem is that currently there's a view among society, and engineers, that we design for a risk factor," Heaton said. "What's the hazard, and I will design according to the hazard. And once I've met certain design criteria, I have confidence that my structure will survive at some given level." So what happens when the big, unexpected event happens? Seawalls are breached. Airports are wrecked. Towns are wiped out. Nuclear plants are swamped. "They believed their risk models, and they shouldn't have," Heaton said. He said engineers should take more of a common-sensical approach to construction design, rather than focusing so much on meeting the specifications dictated by risk analyses. "I think that we've really gotten ourselves off track there," Heaton said. UNCERTAINTIES ABOUND It's tempting to think that Japan has had its "once-in-a-millennium" seismic shock, and that people can relax for the next 999 years. After all, last year's earthquake was big enough to shift Honshu, Japan's main island, as much as 13 feet to the east. It also gave Earth's axis a 6.5-inch readustment and shortened the length of the day by 1.8 microseconds. But Heaton said the geophysical shifts raise additional questions. Here's a potential biggie: Honshu has been subsiding for the past century, and the earthquake just added to the subsidence. That was unexpected, because seismologists assumed that an earthquake would release the crustal strain and result in an uplift. "We know we can't continue to go down at these rates forever, or Honshu would just disappear in a million years or so," Heaton said. Will the island slowly stop sinking and then start rising again? Or will the strain continue to build until another big earthquake releases it? "We don't know the answer to that, but it's a pretty important question," Heaton said. Last May, a team of researchers from Caltech and elsewhere analyzed the seismic data from before and after the quake, and found that significant slip was experienced along a 150-mile length of the Japan Trench fault ó which is about half the length that would have been expected for a magnitude-9.0 event. They also reported that the conditions they saw in the area of the quake's epicenter before March 11, 2011, still exist today in the area to the south, known as the Ibaraki region. "It is important to note that we are not predicting an earthquake here," Caltech's Mark Simons, the study's lead author, said in a news release about the research. "However, we do not have data on the area, and therefore should focus attention there, given its proximity to Tokyo." NASTY SURPRISES Just this week, Japanese researchers reported that Tokyo could be more vulnerable to a magnitude-7 quake in northern Tokyo Bay than they previously thought, and they said older structures should be reinforced to meet more stringent standards. "If a building narrowly fulfills the law's standards, its quake resistance is not high," the Daily Yomiuri quoted seismologist Takuya Nagae as saying. Heaton said it only makes sense to expect further surprises from seismological studies, including some nasty ones. "My experience as a human is that there's a good chance there's something we didn't know. ... It keeps coming up over and over again that there are major holes in our understanding of the system," he said. (Source: MSNBC) Story Date: March 12, 2012

|