|

|

|

|

| April 24, 2024 |

|

In Stanford linguistics study, the accent is on how Californians speak

Like many Californians, architect Ron Vrilakas insists he doesn’t have an accent. “Of course not,” said Vrilakas, 51, a Sacramento native. “Nobody thinks they have an accent. I don’t. Anybody who speaks differently than I do is the one who has the accent.”

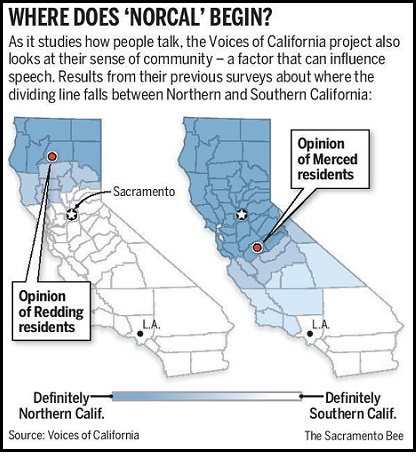

Listening at the conference table in Vrilakas’ airy offices in midtown Sacramento’s landmark Arnold Brothers building, a pair of Stanford University doctoral candidates in linguistics smile and take notes. They’ve heard it before, again and again, actually, during their research for the Voices of California project, which since 2010 has studied regional differences in the way people speak English across California’s Central Valley. “Linguists believe everyone has an accent,” said researcher Annette D’Onofrio. And maybe everyone does. Californians, most of them, at least, know that the way they talk doesn’t fit into the ubiquitous stereotype of the surfer dude-Valley Girl accent. But the state’s residents also tend to overlook the regional differences that do exist in their word choices and speech inflections, as well as the way their personal perspectives on life in California shape their language. Do Sacramentans sound different than people from Redding or Bakersfield or Merced, or Los Angeles? Through Sept. 13, more than a dozen Voices of California researchers are interviewing native-born Sacramento residents, like Vrilakas, whose families have been in the area for several generations, with the goal of documenting their lives and the way they use language. The few prior studies about how Californians speak focused mainly on Los Angeles and San Francisco – the California shown to the world by Hollywood, as if the rest of the state simply didn’t exist, said Penny Eckert, the Stanford professor of linguistics and anthropology who initiated the multiyear project. “That’s iconic California, but it’s not what California is about,” she said. The Central Valley, by comparison, is uncharted California, way off the map from a linguistic point of view: a place long rich in immigration from across the country and around the world; a place with its own down-to-earth values and, perhaps, speech patterns. Another reason that experts have generally overlooked Californians’ varied accents, said Eckert, is that the distinctive speech patterns of booming East Coast cities, such as Boston and New York, take up a lot of linguistic attention. The way people speak there has had a couple of centuries to develop and settle into patterns. The same simply isn’t true of the West. The bizarre result, she said, is that linguistic experts from elsewhere have tended to lump Californians’ accents and dialect in with the way Canadians speak. Yes, Canadians. “We decided that if we didn’t gather serious data, nobody would,” Eckert said. “And it’s particularly interesting in California, because California is so big, so environmentally diverse and so socially diverse.” In previous years, the Stanford linguists fanned out through Merced, then Redding, then Bakersfield, interviewing more than 100 residents in each community. In both Bakersfield and Redding, they found, people’s pronunciation and word choice draws heavily from the heritage of Dust Bowl migration, with a major influence from Southern speech patterns and language choices as compared with how people sound on the California coast. “It’s amazing what people do with language,” said D’Onofrio. “A lot has to do with the way people orient themselves to the place they live,” said her fellow researcher, Teresa Pratt. When people like the place they live, the team has found, they tend to pronounce their words like other people who live there: They want to sound like they belong. Vowel sounds are, it turns out, big in the study of linguistics. In the mouths of Californians, coastal and non-coastal alike, vowels are on the move, from the front of the mouth to the back for some vowels but, in the case of others, the reverse. “Back” has gradually become “bock” in Los Angeles and San Francisco, for example, as the vowel sound has moved away from the front of the mouth. But in San Francisco, “boot” has shifted in the opposition direction, into a slightly softened “beaut” sound. The same shifts are happening in the Central Valley, too, only a little more slowly, said D’Onofrio. “That’s very, very common in California,” she said. “We’re finding that in Redding, too, but it’s not as advanced as on the coast. It’s a change in progress, and with each generation, it’s more advanced. “I think Sacramento is closest to the big cities in that.” In their interviews, the Stanford team records people as they talk about their lives, their jobs, their memories of growing up in Sacramento and how they feel about life here today. It’s basically a nice chat, though one that will be analyzed through a speech database later for vowel sounds and word choice and one that includes being asked to pronounce a long list of telltale words including apricot, coop, pecan, coke, Beth, colt, cult and almond. Researchers also ask participants to divide a state map into the regions they perceive California as having. They’re only now combing through their results from Redding. “When they contacted me, the Voices of California concept reminded me of some of the National Public Radio things, recording people’s stories,” said Vrilakas. “That’s what interested me, that, and the fact that it’s about Sacramento. I’m interested in all things about Sacramento.” A developer who specializes in revitalizing historic urban spaces, including the Arnold Brothers building in midtown that houses his offices and Zocalo restaurant, as well as the Broadway Triangle project in Oak Park, Vrilakas was raised in West Sacramento. He lived in Boston and San Francisco during his 20s before returning to his hometown. His great-grandfather immigrated from Crete, eventually settling on acreage he bought in Red Bluff. His grandfather moved to Sacramento in the 1930s and opened a machine shop. It’s a familiar California story, one of immigration and striving, and Vrilakas has noticed that his relatives who are still more connected with the land are less pretentious in their language. “They’re very suspicious of things that aren’t straightforward and direct,” he said. “If we ever used the word ‘perhaps,’ there would be silence in the room.” (Source: Sacramento Bee) Story Date: September 7, 2014

|