|

|

|

|

| May 5, 2024 |

|

Dallas Ebola patient dies; U.S. to screen for fever at 5 airports

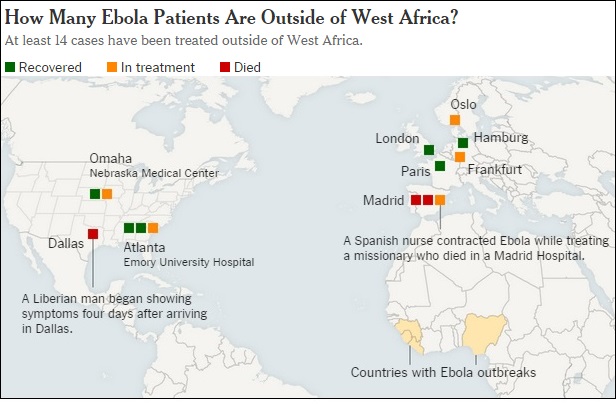

DALLAS--Thomas Eric Duncan, 42, the patient with the first case of Ebola diagnosed in the United States and the Liberian man at the center of a widening public health scare, died in isolation at a hospital here on Wednesday, hospital authorities said.

Mr. Duncan died at 7:51 a.m. at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, more than a week after the virus was detected in him on Sept. 30. His condition had worsened in recent days to critical from serious as medical personnel worked to support his fluid and electrolyte levels, crucial to recovery in a disease that causes bleeding, vomiting and diarrhea. Mr. Duncan was also treated with an experimental antiviral drug, brincidofovir, after the Food and Drug Administration approved its use on an emergency basis. “The past week has been an enormous test of our health system, but for one family it has been far more personal,” Dr. David Lakey, the commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said in a statement. “Today they lost a dear member of their family. They have our sincere condolences, and we are keeping them in our thoughts.” The mayor of Dallas, Mike Rawlings, also offered some assurance to Dallas residents. “I remain confident in the abilities of our health care professionals and the medical advances here in the U.S.,” Mr. Rawlings said, “and reassure you we will stop the Ebola virus in its tracks from spreading into our community.” After Mr. Duncan arrived at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport on Sept. 20, he set off a chain of events that raised questions about health officials’ preparedness to detect and contain the deadly virus. His case spread fear and anxiety among those he encountered, however briefly, and turned the places, vehicles and items he touched into biohazardous sites that were decontaminated, dismantled, stored or, in some cases, incinerated. Mr. Duncan went to the airport in Liberia on Sept. 19 for his flight to the United States, landed in Dallas the next day and first went to the emergency room at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital feeling ill on Sept. 25. He was released by the hospital, which had failed to view him as a potential Ebola case for reasons that remain unclear. He returned there and was admitted Sept. 28 after his condition worsened. Mr. Duncan spent nearly two decades separated from the woman he had traveled to Dallas to be with, Louise Troh, 54, with whom he had a son. The couple were apparently rekindling their relationship. Yet in the last days of Mr. Duncan’s life, Mr. Duncan and Ms. Troh remained more apart than together. Each had been quarantined because of the risk of spreading Ebola, Mr. Duncan in virtually his own hospital ward and Ms. Troh in a four-bedroom home on a remote property that state health officials prohibited her, her 13-year-old son and two others from leaving, under threat of prosecution. Mr. Duncan had been a driver at a cargo company in Monrovia, the Liberian capital, living alone in a small room he rented from the parents of Marthalene Williams, 19. A simple act of kindness probably exposed him to the virus that has killed more than 3,000 people in West Africa. In Monrovia, neighbors and Ms. Williams’s parents said Mr. Duncan helped the family take Ms. Williams to and from a hospital on Sept. 15, shortly before she died of Ebola. Some of the men and women who had direct contact with Ms. Williams, and who were also in contact with Mr. Duncan, have also died, including Ms. Williams’s brother, Sonny Boy Williams, 21. Mr. Duncan helped carry her while she was sick with the virus and convulsing. The disease is contagious only if the infected person is experiencing active symptoms. Local, state and federal officials have expressed confidence that they have been able to limit the spread of the disease in Dallas and said that none of the people they were monitoring had shown any symptoms of Ebola. Officials are monitoring 48 people in the Dallas area, most of whom have not been quarantined but are instead staying home while they are under observation. Ten of those are considered high risk, including seven health care workers and three relatives and community members who had contact with Mr. Duncan. The other 38 are considered low risk, and include people who may or may not have had direct or indirect contact with Mr. Duncan. One of those 38 is Michael Lively, a homeless man who rode in the ambulance that took Mr. Duncan to the hospital after the vehicle dropped Mr. Duncan off but before it was taken out of service and disinfected. Mr. Lively briefly disappeared on Sunday before he was found by law enforcement officers, an indication of the unease being felt by some of those being monitored. U.S. to begin Ebola screenings at 5 airports ATLANTA--Federal officials said Wednesday that they would begin temperature screenings of passengers arriving from West Africa at five American airports, beginning with Kennedy International in New York as early as this weekend, as the United States races to respond to a deadly Ebola outbreak. Travelers at the four other airports, Washington Dulles International, O’Hare International, Hartsfield-Jackson International and Newark Liberty International, will be screened starting next week, according to federal officials. The screenings, which will include taking the passengers’ temperatures with a gun-like, noncontact thermometer and requiring them to fill out a questionnaire after deplaning, will be for people arriving from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, the three countries hardest hit by the epidemic. About 90 percent of the people arriving from the three countries come through the five airports, officials said. Kennedy Airport alone has about 43 percent of the travelers. The second-highest share of visitors, 22 percent, come through Washington Dulles. Over all, their numbers are relatively small. Of the roughly 36,000 travelers who left the three countries over the past two months, officials said, about a quarter came to the United States. Of those, 77 had symptoms, such as a fever, consistent with early-stage Ebola, but none turned out to have Ebola. Most of the fevers were related to malaria, a disease spread by mosquitoes. The airport screenings are the federal government’s first large-scale attempt at improving the safety at American ports of entry. The C.D.C. will send personnel to airports to perform the screenings, and Coast Guard members will be deployed to help in the coming weeks. It is the first time that health authorities in the United States have taken the step of monitoring the temperature of people arriving at American airports, and the policy carried broad implications for health departments across the country. How to respond to someone with a temperature will be up to local health departments, officials said. Local health officials may decide to quarantine a traveler, something that is legal under American law, or to transport a traveler to the hospital. Officials are also working to coordinate efforts with countries that receive connecting flights from West Africa with United States-bound passengers so that the C.D.C. questionnaire can be distributed internationally, officials said. (Source: The New York Times) Story Date: October 9, 2014

|