|

|

|

|

| April 25, 2024 |

|

Program to solve veteran homelessness expanding

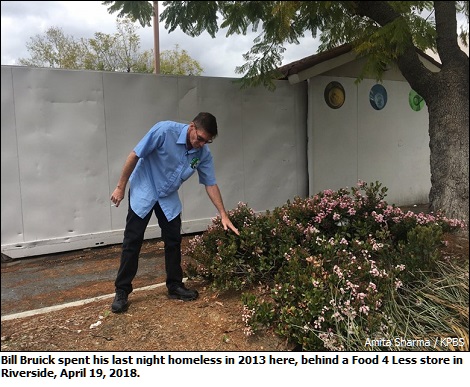

RIVERSIDE - Army veteran Bill Bruick spent his last night homeless lying on a tiny patch of dirt, now festooned with a pink flowering shrub behind a Food 4 Less grocery store in Riverside.

“There were no bushes,” Bruick said, pointing to the exact spot still remembering the lump in the ground. “I slept right here. I liked it because nobody could really see me back here. Nobody ever parked back here. I got lucky you know.” That night in 2013 capped 10 years of living outside a shopping center for the 51-year-old Bruick who resembles a young Charlton Heston. There are around 40,000 homeless veterans in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. More than 11,000 of them live in California. The state has seen a 17 percent rise in homeless vets since 2016. The city of Riverside is the only city in California to end veteran homelessness, according to the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. It is one of 62 communities in 32 states to do so. Many homeless vets suffer from substance abuse and mental illness. Bruick said depression and alcoholism had hobbled him since leaving the Army in 1996. He filled his days drinking beer and vodka. He started early. Seven stints of rehab did nothing for Bruick. But one bout of alcohol poisoning and a letter from his two daughters in Germany expressing a desire to visit inspired change. “I was like, `Wow, I’ve got to do something,’” Bruick said. “I don’t want them seeing me in this state.” Around the same time, Riverside was in the midst of embracing then-President Barack Obama’s push to the country’s mayors to end veteran homelessness. “As a veteran myself, it was easy to for me to accept that challenge,” said Riverside Mayor Rusty Bailey. He had also seen his two family friends’ anguished descent into homelessness. And he said when he was in the ninth grade, his church would feed the homeless on Sunday nights. Bailey said he wanted the city’s outreach workers to get personal with homeless vets, by knowing their names and repeated visits, sometimes as many as 50. Then came offers of a place to live. It is an approach called Housing First. The idea is to get vets off the street or out of shelters and into permanent housing before addressing substance abuse or mental health issues. “We have the success stories to prove that Housing First is the right policy for ending homelessness,” Bailey said. Through the project, veterans had access to VA housing vouchers. But Bailey still had to convince apartment owners to rent to people coming off the streets. “I pounded on the table and said it’s inexcusable to have veterans in our city who don’t have homes,” Bailey told KPBS. “Landlords, where are you at? And many of them stepped up.” Once they got a place to live, vets were paired up with social services, from mental health to substance abuse to job training. By the end of 2016, Riverside had housed all 89 of its vets. The city’s share of the feat was $348,000. Bruick was one of the Riverside program’s early beneficiaries. He went to rehab for the eighth time. Today, he lives in a one-bedroom apartment in Riverside with his fiancee. And he works at a facility that houses vets until they’re placed in permanent homes. Mayor Bailey is now applying what the city learned through housing veterans to Riverside’s 400 chronically homeless people. The Riverside City Council backed a plan in March that would place them in housing before offering them social services. Story Date: May 23, 2018

|