|

|

|

|

| April 20, 2024 |

|

San Francisco bans facial recognition surveillance technology

SAN FRANCISCO--The City of San Francisco is the first major city to ban local government agencies’ use of facial recognition, becoming a leader in regulating technology criticized for its potential to expand widespread government surveillance and reinforce police bias.

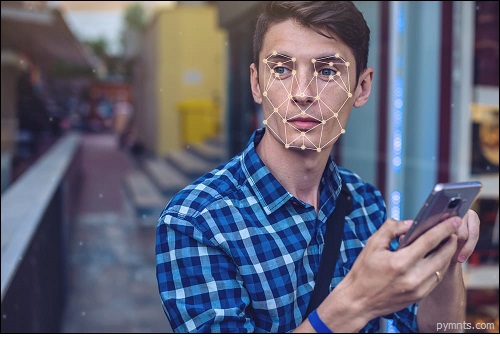

The “Stop Secret Surveillance” ordinance passed 8-1 in a vote by the city’s board of supervisors Tuesday. The ordinance will implement an all-out ban on San Francisco city agencies’ use of facial surveillance, which tech companies such as Amazon and Microsoftcurrently sell to various US government agencies, including in Amazon’s case, US police departments and in Microsoft’s case, a US prison. These technologies can detect faces in images or live video streams and match those facial characteristics to someone’s identity in a database. Today, facial recognition technology is widely used by the Chinese government for Orwellian mass surveillance of ordinary citizens in public life, most alarmingly to target the Uighur Muslim ethnic minority in what’s been called “automated racism.” In the US, the tools are far less ubiquitous but becoming increasingly popular with law enforcement agencies. Dozens of local police departments across the US use the technology to match driver’s license pictures and mug shots to criminal databases. It’s also used (in some cases by private citizens, not police) to monitor crowds at events such as protests, shopping malls, and concerts to identify potential suspects in real-time, which has caused alarm with civil liberties advocates who say that can have a chilling effect on free speech. The ban is just one part of San Francisco’s surveillance oversight ordinance, which will also require city agencies to get city approval before purchasing other kinds of surveillance technologies, such as automatic license plate readers and camera-enabled drones. It won’t stop private citizens or businesses, however, from using these facial recognition systems. (So, Taylor Swift, if you’re reading this, you’re still in the clear to welcome San Francisco concertgoers with a face scan.) And of course, everyday San Franciscans can continue to willingly participate in pervasive facial recognition technology like the rest of us when we unlock our iPhones, or tag a suggested friend in a Facebook photo, for example. Supporters of facial recognition technology say that it has the capability to help police departments more efficiently identify and arrest criminal suspects, but critics point to examples of misuses that they say prove it can do more harm than good. In a particularly egregious example, the ACLU ran a test of Amazon’s facial recognition software and found it incorrectly misidentified 28 black members of Congress as criminals. Researchers at MIT found that, overall, the software returned worse results for women and darker-skinned individuals (in both cases, Amazon has disputed the findings). And in places like Maryland, police agencies have been accused of generally using facial recognition technology more heavily in black communities and to target activists, for example, police in Baltimore used it to identify and arrest protestors of Freddie Gray’s death at the hands of law enforcement. Other cities are following San Francisco’s lead. In nearby Oakland, and across the country in Somerville, Massachusetts, local city councils are set to vote on bills that would implement a similar ban. The San Francisco Bay Area is home to a robust network of civil liberties and racial justice groups, so it’s no surprise that city governments there are leading regulation on technology that could strip privacy and reinforce societal inequalities. What the ban will — and won’t — do The facial recognition ban will most directly limit the San Francisco Police Department, which doesn’t currently use facial recognition technology, but has tested it in the past. If the ordinance passes, SFPD won’t be able to restart any testing of such tools. That means that they won’t be able to, say, connect security cameras installed on public streets to image-processing technology and databases of criminal mugshots. The ordinance will also restrict local police from sharing some information with federal agencies such as Immigration and Customs Enforcement, according to Matt Cagle, a technology and civil liberties attorney for the ACLU. Cagle said in a public hearing on the ordinance that the immigration agency responsible for deporting undocumented immigrants has previously requested information from the San Francisco Police Department. San Francisco is a sanctuary city — which means that it in most cases, it doesn’t cooperate with federal agencies like ICE to deport unauthorized immigrants. However, restrictions on surveillance technology won’t apply at the San Francisco International Airport, where federal agencies such as the Transportation Security Administration and Customs and Border Patrol have jurisdiction, and are free to use facial recognition systems and biometric scanners as they please. The spread to other cities In many ways, San Francisco, and California in general, is setting a trend for urban areas across the nation that are increasingly demanding more oversight of surveillance technology. Just under a dozen US cities, including Seattle, Nashville, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, have passed laws using that framework to give their local officials more power to regulate the use of surveillance tools. And about 20 more cities are actively working on similar legislation. Meanwhile, many have called for federal legislation, including Microsoft, a major vendor of facial recognition technology. But at least in the short-term, a patchwork of local regulation seems more likely and achievable, according to privacy researchers and advocates in this space. (Source: VOX) Story Date: May 24, 2019

|