|

|

|

|

| April 26, 2024 |

|

California fire season could last into December

RIVERSIDE - For a third straight year, California’s fire season is ramping up when it should be winding down.

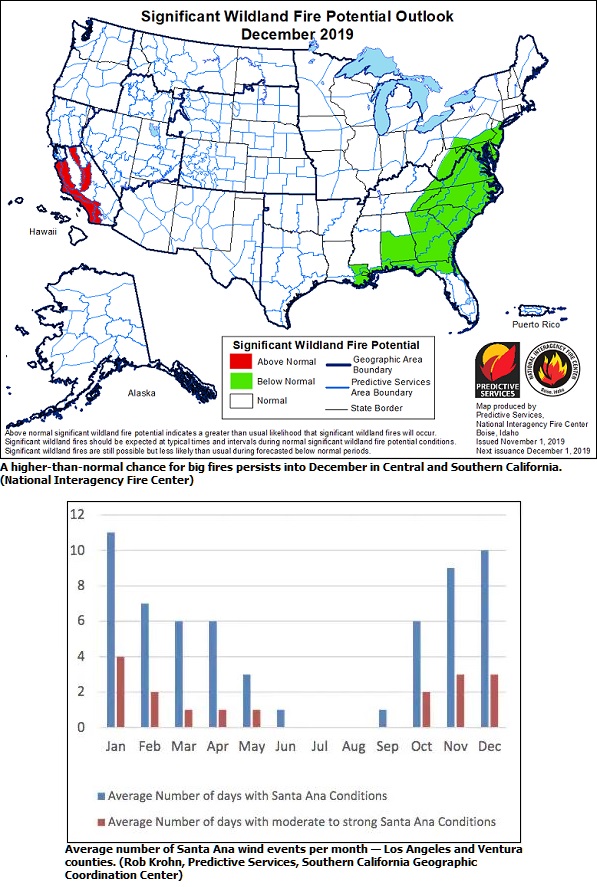

After an onslaught of wind storms and flurry of blazes, large swaths of the state are now extremely dry and primed to burn until winter rains arrive to quell the danger, when and if they do. Just a month ago, it seemed like California might avoid another bad fire season. Showers swept over the far northern part of the state, snowfall blanketed the slopes of Lassen National Park, and much of the state got a blast of wintry air. But then that jet stream pattern shifted east, and three weeks of dry October windstorms followed, plunging California into a severe fire season, one that could last well into November, and possibly even through December. “This may be a long fall and winter across California for both the firefighting community and the general public in terms of coping with the threat of fires,” reads the latest Predictive Services wildfire outlook released Nov. 1 from the Southern California Geographic Coordination Center in Riverside. Meteorologists there now expect a higher-than-normal chance for big fires in December, with a late start to the rainy season looking increasingly likely. In Ventura County, firefighters have been battling the Maria Fire (now 80 percent contained), which ignited Halloween eve at the tail end of the season’s most potent Santa Ana wind event. The largest Southern California wildfire of the year at nearly 9,500 acres, the Maria Fire may be a preview of late-season blazes if conditions don’t improve. October winds set stage for November and beyond California’s incredibly long siege of fire weather began in the Sacramento Valley on Oct. 9 and ended when the last red flag warning for high fire danger expired Saturday at 6 p.m. in Los Angeles and Ventura counties. Last week, the strongest offshore winds of the season pummeled the state from north to south: A 102 mph gust was recorded near the Kincade Fire in Sonoma County last Sunday, while the mountains of Southern California had gusts topping 70 mph Wednesday. In Northern California, there were more dry wind events in October 2019 “than in any single month in the past 30 years,” according to a Predictive Services report for that region released Friday. Southern California’s Santa Ana winds roared for 10 days last month, six of those classified as “moderate” or “strong” (normal for the month is two moderate to strong Santa Ana days). While the fiercest winds have subsided, they left much of the state a tinder box, in part because they brought near-record dry air. The windiest, and now driest, corridors can be seen in a recent statewide map of the Energy Release Component, a measure of how hot a fire will burn based on vegetation dryness. Anything above the 97th percentile (dark orange and browns) is considered ultra-flammable, and forest service data now shows many regions have surpassed record dry, including the Sacramento Valley, the San Francisco Bay area, the southern Sierra Nevada and the coastal ranges of Southern California. October’s desert-like weather pattern brought a mix of ingredients that can easily draw moisture from plants and into a thirsty atmosphere: high winds, extremely dry air, sunny days and high daytime temperatures. This drying effect is captured in maps of the Evaporative Demand Drought Index, where dark red shows record values going back to 1979. This month, a stagnant, warm weather pattern could make the situation even worse. Desiccating conditions, sunny, warm and dry, are set to linger into November, although no significant offshore wind events are in the forecast ... yet. With a ridge of high pressure building over the West Coast, meteorologists are expecting above-normal temperatures, light wind and widespread dry air for at least the next 10 days. There’s a good chance that warmth could last through the month, according to the Climate Prediction Center. A parched landscape meets peak Santa Ana season The longer-term forecast is particularly worrisome for Southern California because it means the landscape would be severely dry when Santa Ana winds typically peak. Santa Ana winds are most common, and stronger, from November through February, when cold air and high pressure dominate the Great Basin region in northern Nevada and Utah, driving these powerful, dry winds southwest into Southern California. “Santa Ana season and the rainy season go hand-in-hand,” said Matt Shameson, a fire meteorologist at the Predictive Services office in Riverside. The biggest wind events usually strike from mid-November through February, he said, but “it’s normally not an issue because we’ve gotten a decent amount of rain.” But those cool-season winds have become a problem in recent years. Autumn rains were nonexistent when the Thomas Fire sparked Dec. 4, 2017, amid the longest-observed Santa Ana wind event on record (12 days), eventually burning 281,893 acres in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties and destroying 1,063 structures. Computer models have indicated a later start to California’s rainy season in a warming climate, as heavy precipitation becomes more concentrated in the winter months, with less rainfall in the fall and spring. Shameson said meteorologists have noticed that late rainfall arrival in the past five years or so. And the upcoming winter is projected to be warmer and drier than normal. “I’m expecting to get more large fires before we get rain,” he said. (Source: The Washington Post) Story Date: November 17, 2019

|