|

|

|

|

| April 20, 2024 |

|

College students, seniors and immigrants in California miss out on food stamps

SACRAMENTO - A college student in Fresno who struggles with hunger has applied for food stamps three times. Another student, who is homeless in Sacramento, has applied twice. Each time, they were denied.

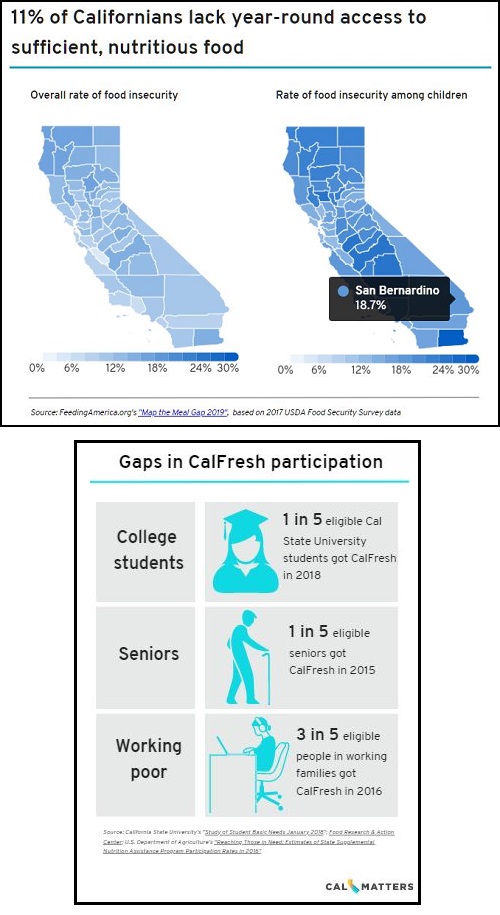

A 61-year-old in-home caretaker in Oakland was cut off from food stamps last year when her paperwork got lost. Out of work, she can’t afford groceries. While picking up a monthly box of free food, a 62-year-old senior in San Diego told outreach workers that she won’t apply for food stamps because she worries that it might prevent her from qualifying for U.S. citizenship. All told, roughly 1.6 million Californians are not getting help from the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, known as CalFresh here, even though they are eligible. That means 28% of people with poverty-level budgets didn’t receive the food assistance they needed, according to 2017 state data. At the bookends of adulthood, college students and seniors increasingly struggle to pay their bills yet they are among the groups most likely to miss out on the food stamps they qualify for, according to interviews with more than a dozen outreach workers and state and county officials. Obstacles also face immigrants, working families and homeless people, experts said. When these categories overlap, the hurdles to obtaining food stamps are often higher. At California State University campuses in 2016, just 5% of students were getting food stamps even though one in every four was eligible. For seniors in California, just 19% got the assistance, compared with 42% of seniors nationally, according to 2015 data. And citizens who are immigrants are less likely to sign up than those who were born in the United States. For those living on the edge, food stamps can make a big difference: The average CalFresh household each month earns $735 and gets $272 in food stamps, which amounts to $3 per meal. A family of two qualifies with $16,920 per year after paying expenses such as housing and childcare. “On a human level, what that means is that we continue to allow Californians to go without food,” said Jessica Bartholow, a policy advocate at the Western Center on Law and Poverty. California’s low enrollment is not inevitable. Nine states, including neighbors Oregon and Washington, enrolled nearly every eligible person in 2016, according to federal data, while California had the fifth lowest rate in the nation. Nearly 4.4 million Californians lack reliable access to sufficient food, including 644,300 seniors and 1,638,430 children. In a statewide survey of college students, 35% were food insecure. Each story of someone who loses out on food stamps provides a lesson for how county officials and state lawmakers could clear the roadblocks that prevent people from getting help. In California, about 61% of eligible working poor people participated in CalFresh in 2016, compared to 75% across the country, according to federal data. Incomplete applications and churn are especially common among homeless people, who often lack an address and cellphone, said Amy Dierlam, CalFresh outreach director at the River City Food Bank, a lifeline for Sacramento’s growing homeless population. Some have trouble keeping track of papers and appointments due to disability, mental illness or addiction. The fear has made it harder to get CalFresh to immigrants. But the puzzle of federal eligibility requirements for non-citizens has long been difficult for county workers to explain in English, let alone in other languages. Among U.S. citizens who fall below the income limit for the program, the rate of immigrants who reported participating in CalFresh is 70% that of people born in the U.S., according to 2018 California Health Interview Survey data. Counties can fight the chilling effect by ensuring that all paperwork is well-translated into locally-spoken languages, said Almas Sayeed, deputy director of California Immigrant Policy Center. She said county offices dedicated to providing immigrants with a welcoming space in Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Clara provide a model. Limited knowledge of the program and the intimidating amount of paperwork also are significant barriers for seniors, said Lorena Carranza, CalFresh outreach manager at the Sacramento Food Bank. One recent policy change may help educate seniors and dispel myths. Until June of this year, low-income seniors and disabled people receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) were barred from getting CalFresh. But California lawmakers voted last year to expand the program to SSI recipients, so counties and food bank mobilized a statewide enrollment campaign. As of October 1, nearly 243,000 SSI recipients had enrolled. (Source: CalMatters) Story Date: November 13, 2019

|